by Hope Mohr

/////

This post is the first in a series reflecting on HMD’s ongoing work of shifting the organization to an equity-driven model of distributed leadership. These reflections come in the midst of the work, without a sense of where it will take us.

I’m writing in the first person. The writing therefore reflects my personal blindspots. It’s also only 1/3 of the picture: I’ve been moving through this work in collaboration with my co-directors, Karla Quintero and Cherie Hill, who have their own experiences of this work that they’ll share as they feel called to do so. (They have also reviewed this post). I want to thank Karla and Cherie for their partnership, vision, and generosity in doing this work. I want to thank consultant Safi Jiroh of LeaderSpring for holding space for us to do this work. And I want to thank the artists and advisors who have been our thought partners and open-hearted participants in this ongoing process (in no particular order): Bhumi B. Patel, Suzette Sagisi, Megan Wright, David Szlasa, Tracy Taylor Grubbs, Chibueze Crouch, Zoe Donnellycolt, Hannah Ayasse, Jarell Phillips, randy reyes, Daria Garina, Julie Tolentino, Gerald Casel, Jen Norris, Jane Selna, Belinda He, Tristan Ching, and Julian Carter.

/////

HMD’s process of moving to a model of distributed leadership began about a year ago. When HMD made the announcement that we were beginning this work (see this blog post), I received a host of questions and comments from donors, Board members, patrons, and artists that included:

“What does this actually mean?”

“Aren’t you afraid of alienating donors?”

“What about you as an artist?”

From white people, I got this question: “I don’t know where I fit into this new vision of the organization.”

And, before the killing of George Floyd, also this question (also from a white person): “Why are you doing such political work right now?”

Response from artists of color has been overwhelmingly positive.

I’m writing these posts so that this internal work is transparent and accessible to the public. The work of re-structuring arts organizations must be outward-facing so the learning doesn’t happen merely behind closed doors. Value-driven distributed cultural leadership, by its nature, is necessarily more than an internal affair among staff: it is about giving power to artists and in particular, artists who historically have not been in positions of power within cultural institutions. And so this work must happen in relationship and in dialogue with an organization’s community. (Part of the work of distributed leadership is clarifying who your community is).

Sharing and giving away power in an arts organization is messy and difficult. In today’s fraught call-out culture, it’s tempting to want to hide our shortcomings and vulnerabilities. I am writing from inside the imperfection and unknowing as a way to normalize the fallibility of anti-racist work.

Another reason I’m writing this series of blog posts is: white people need to talk to other white people about giving up power. For too long, people of color have been called upon to do this educational and emotional work. In the words of feminist writer Judit Moschkovich, “it is not the duty of the oppressed to educate the oppressor.”[i] There’s an insidious tendency, even in the work of de-centering whiteness, to center whiteness. I don’t want to focus on whiteness in the same way it’s centered in our culture, but rather, in the words of writer Claudia Rankine, with the awareness that “[w]hiteness is the problem, and whites are the ones who need to fix themselves. So you sort of need to center them.”[ii]

/////

There are a lot of calls right now for white cultural leaders to step back and step down in order to dismantle white supremacy. In some cases, this is entirely appropriate. In other cases, the abrupt disengagement of a white leader is not necessarily the ideal course of action. I want to unpack the complexity of stepping back.

Knowing when and how to “step back” can be confusing and difficult for many white people. After years of struggling to build their careers, many white artists feel wronged if they forego opportunity. For white women, cultural equity and feminism may feel at odds: stepping back may feel contrary to feminist teachings that tell women to take up space. These complexities can contribute to a failure of allyship even when intentions are good. [iii]

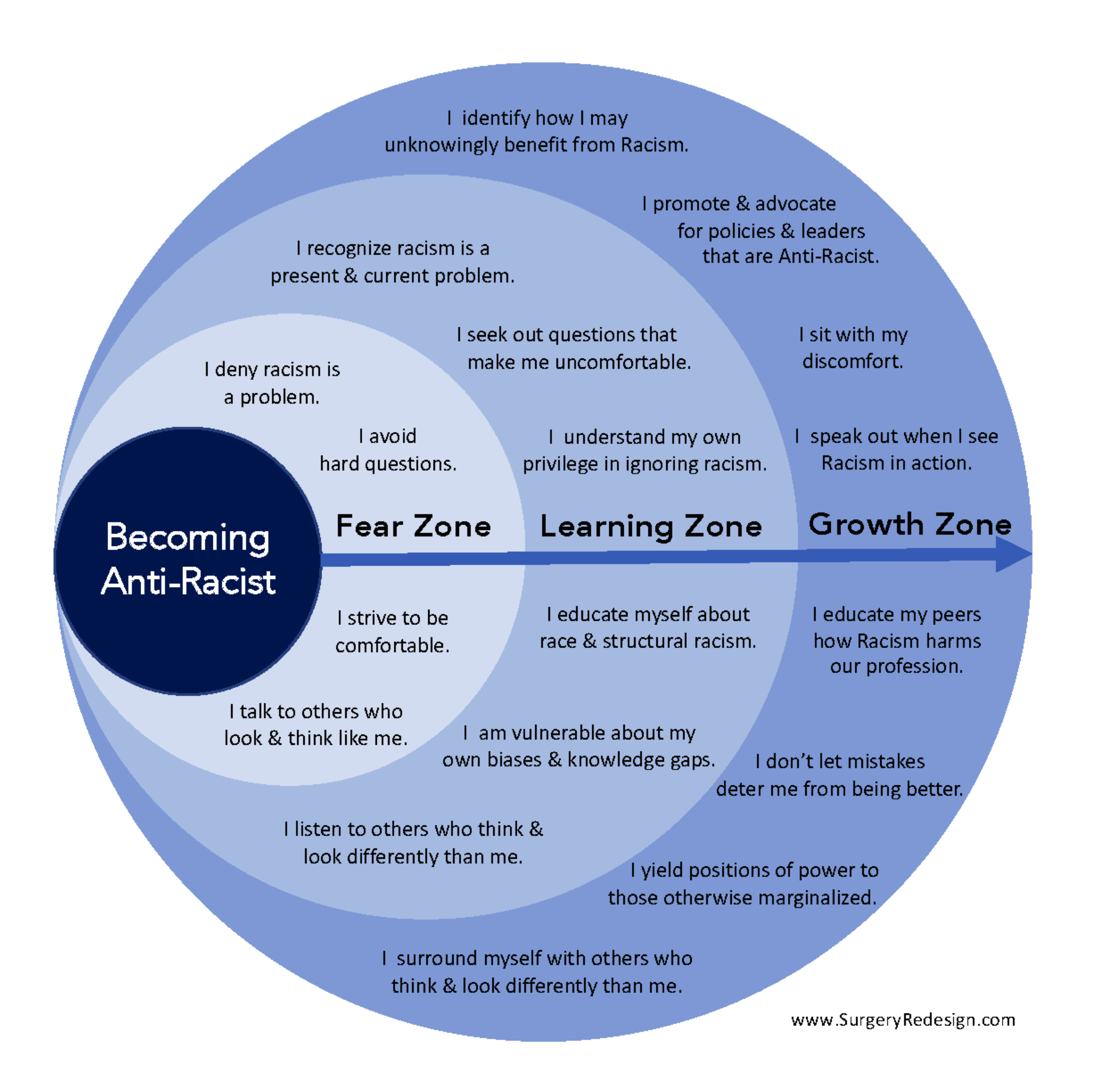

I’m interested in de-centering whiteness not as a way to hide, but as a way of holding space for others while remaining engaged and accountable. Sometimes white people use “de-centering whiteness” to justify a retreat from difficult conversations. When faced with challenges to their power, white people can assume a variety of defensive postures, including: denial, defensiveness, perfectionism, retreat into intellectualism, self-absorption, silence, criticism, and numbness. [iv] These defensive postures prevent white people from engaging fully in the work of confronting and changing existing power dynamics.

In my own experience of transitioning HMD from a historically hierarchical arts organization into a model of distributed leadership, I have discovered that inside stepping back, there is a choice. I can step back and withdraw emotionally. Or I can step aside and stay accountable and engaged. At times, a better image for the work might be “stepping to the side”: making space for other voices while staying in relationship.

It’s crucial that we not use de-centering whiteness as a way of bringing people of color into toxic structures. I don’t want to make, as Tomi Obaro writes, “a few token hires who are placed into the same system, forced to do all the hard work of undoing years of systemic harm, and eventually burn out and leave the [arts] altogether, thoroughly disillusioned.” Obaro continues: “What about a justice that is more radical, more forward-looking, one that does not perpetuate existing power structures with a slightly browner tinge?” Let’s de-center whiteness to make space for new models.

In making space for other voices, white people must be mindful not to dump the work on the shoulders of people of color without ensuring that capacities and support systems are in place. Also, when a white cultural leader steps back from socially engaged work, it also threatens to reify the assumption that socially engaged art is not white people’s work, but the domain of people of color. How can white people redistribute power without avoiding the structural work of anti-racism? In stepping back, how can white people not withdraw our resources, networks, and position, but connect people of color directly with these existing assets? When white leaders in the arts step back, it creates crucial opportunities for white donors to demonstrate more inclusive cultural philanthropy by investing in leaders of color, not only in historically white-led organizations undergoing leadership change, but also in organizations founded by and for people of color. (See the Helicon Collaborative’s Not Just Money: Equity Issues in Cultural Philanthropy for more insights into redistributing cultural funding).

In undertaking this work, I’ve faced resistance from white donors, many of whom are friends and family. Some don’t understand what this work has to do with me as an artist or with them as arts patrons. In response to a survey that HMD sent out regarding our shift to distributed leadership, one respondent said that they had always thought HMD’s purpose was to be a place for me to express my artistic vision; was it necessary for me to give up this vision to address inequities?

Let’s imagine a space where artistic excellence and politics are not mutually exclusive. Artists from historically marginalized communities often have no choice but to intertwine politics with their art. Their art is saturated with history by necessity because there is no possibility of living otherwise. In contrast, for many white artists, integrating artmaking and politics feels optional. In fact, there’s a long tradition of white artists believing that they need to isolate themselves from politics in order to create (this is what author Jess Row refers to as the “white autonomy of the imagination”). Let’s change this double standard. Let’s expect that repairing social and cultural inequities is a necessary part of my vision as a white artist.

HMD is well positioned to do this work because we have strong relationships both with people in positions of power (funders and wealthy white donors, for example) and with artists who identify as coming from historically marginalized communities. What an excellent opportunity to invest energy and resources where they are most needed. What an excellent opportunity for dialogue and learning. To HMD’s supporters, I want to say: this is our work. This is creative practice.

Now is the time to expand the mission of the arts. An artist’s work right now is not to burrow inward, but to open outward. We need to find new terms on which to make art—new terms on which to exist. Some days this does not look like making art, but having conversations about white accountability. Other days it looks like exploring an idea of craft that does not come from the editorial impulse, but from a place of permission: welcoming in mess and that which does not “fit.” Other days it looks like questioning the aesthetic lineage that sits in my cells.

The point is, it’s all creative practice. And it’s all necessary.

The work of value-aligning arts organizations is not only about dismantling the walls that separate us, but also the walls inside of us.

/////

Stay tuned for the next post in this series: Actions toward Distributed Leadership

/////

[i] Judit Moschkovich, “--But I Know You, American Woman,” in Gloria Anzaldua and Cherie Moraga, eds., This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, (Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 2n ed., 1981), 79.

[ii] Salamishah Tillet, “Claudia Rankine Flies the Unfriendly Skies,” N.Y. Times, March 11, 2020, AR 18.

[iii] See Aruna D’Souza, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, (Badlands, 2018) (setting forth case studies in how white allyship has failed in the visual arts world).

[iv] I take this from the wisdom, teachings, and resources of the anti-racism groups Courage of Care and Stronghold. For more information visit http://courageofcare.org/ and https://www.wearestronghold.org/

HMD is partnering with LeaderSpring in our equity-driven work toward distributed leadership. More information about LeaderSpring is available at https://www.leaderspring.org/.

/////

A version of this content will appear in my book, Curating as Community Organizing, forthcoming from the National Center for Choreography and the University of Akron Press.