This zine was distributed at the final Dancing Around Race gathering on February 28, 2019.

“If whitespace is the common space, safe space is other. Thinking in line with disturbance ecologies, safe space has developed out of a landscape of ruin.”

-Nikima Jagudajev

——————————————————

Dancing Around Race – Interrogating Whiteness in Dance (excerpted from a longer paper)

by Gerald Casel

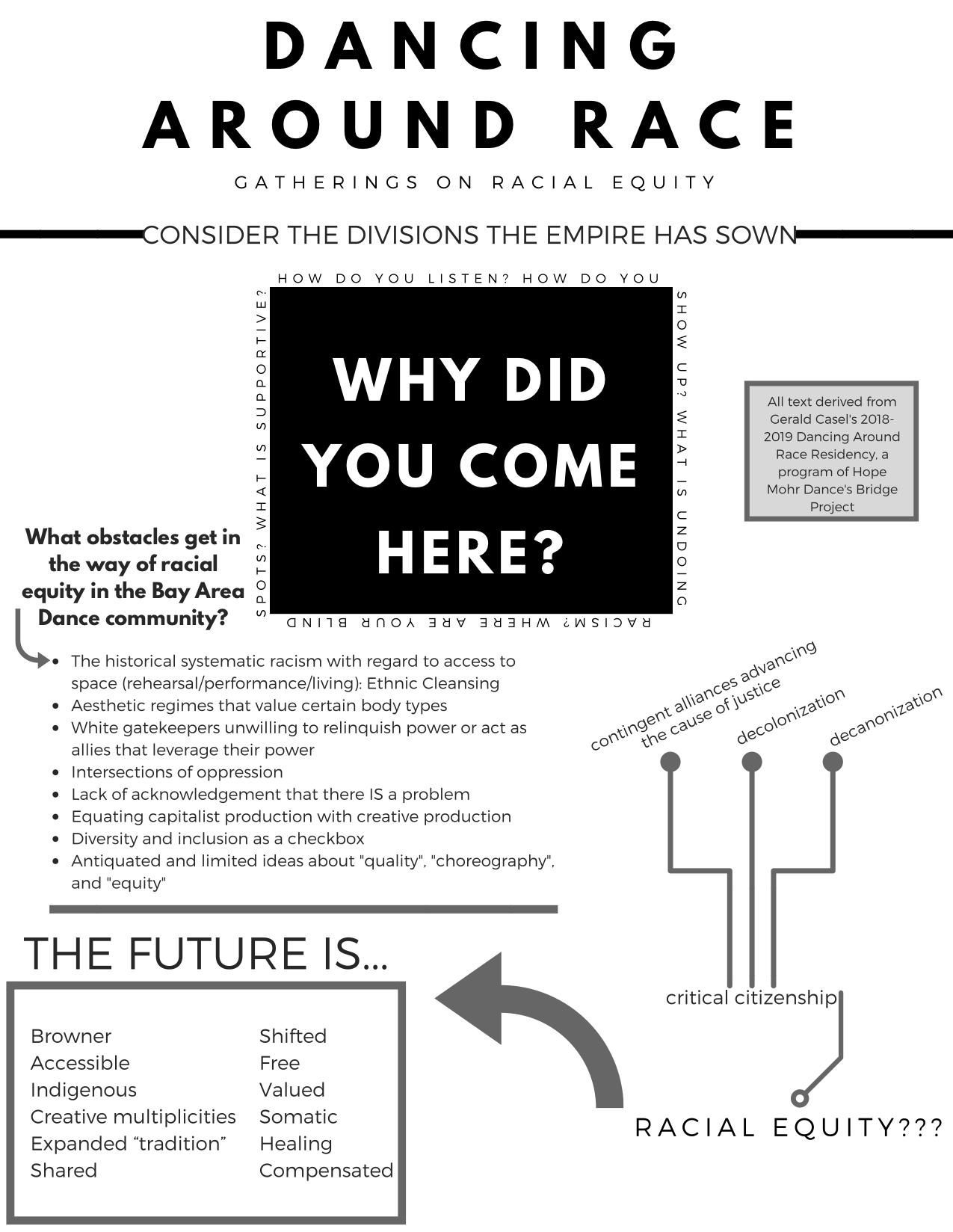

Dancing Around Race explores the socio-cultural dimensions of race within the interconnected fields of choreography, dance presentation, dance training, funding, curatorial practices, and dance criticism in U.S. contemporary and postmodern dance. Looking closely at the Bay Area dance ecology and working with a systems thinking approach, this inquiry examines how various elements contribute to or inhibit equitable distributions of power, access, and representation with regard to race. Specifically, I examine how the invisibility of Whiteness preserves segregation through the legacies of ethno-racial hierarchies produced by the racialized history of contemporary and postmodern dance in the U.S. Addressing themes that highlight issues of race and identity in my choreographic research and extending that to my engagement with the community is the focus of this work. One of the aims is to build critical consciousness that transforms institutions so that they are more equitable and also, so that artists are valued, supported, and are able to create work that cultivates emancipatory practices despite their ethno-racial identity.

When describing Whiteness, I am not referring to White people, but the systemic structures that privilege individuals who self-identify as White, are identified as White by others, or White-passing.

Throughout this past year we have been interested in unveiling Whiteness and how, more specifically, its invisibility affects the dance communities in the San Francisco Bay Area. We have been interested in interrogating and undoing systems that promote hegemonic power structures that reify racist ideologies; it is useful to untangle them to examine how common personal struggles can intersect and affect larger narratives that have shared goals of equity and inclusion. Since many individuals and institutions claim to be inclusionary, it is important to principally acknowledge inequity by looking within while also critiquing the external effects of institutional regulations. This way of collectively zooming the lens in and out to see the micro and macro levels of systemic structures assists in applying more flexible, adaptable, and nuanced modes of conceiving and interpreting these complex issues of race and identity and how to find solutions through coalitional efforts that foster counter-hegemonic practices. I ask, “What does equity look like in public? What does equity look like in practice?”

——————————————————

what it do brown body

by SAMMAY

what does the brown body mean to you?

eyes wide towards an imagined horizon

limbs outstretched reaching only for what’s true

what does this brown body do for you?

a forgotten shade of the spectrum

unacknowledged in the rainbow

of dreams unspoken

discernment flowing in streams

in her mother’s cry

in the mind’s eye

of her ancestors

what does this brown body mean to you?

righteous veins of resilience

cultivated through war

loss

death

miscarriage

mismarriage

buried secrets

and

“it was an accident”

unraveling

(we are unraveling)

unearthing the meaning deep beneath her skin

she is finding what it means

what it feels like

like supple mangoes

early fallen from the tree

like heaven manifestations

in the everyday mundane

what does this body mean to them?

have they forgotten she was cut from her stem?

a blossom unripened in her bosom

her colors struggling to maintain

v i r a c i o u s l i l m a m i

their vibrancy

her breath

be her lifeline

and without (her roots) she is running on Empty

trekking carefully

not to misstep/mis-rep

and fall down into the abyss

of amnesia

a.k.a triggermania

the epigenetics not in her favor

but theirs

//

what does this body do for you?

you really wanna know what it do?

what life be like

you can’t fit this shoe

so she dance barefoot

until she splinters and finds

memory

tragedy

unexpress-said despair

her grandmother’s dementia

her great grand lolo’s long hair

she don’t dance for the applause

could care less about the game

she plant seeds each time her toes

meet mama earth’s great mane

this be her bidding from the Great Ones

a lifelong song of nostalgic cadence

where beauty lives in darkness

and the only way to get there is to

scrape.

scratch.

slice

slice

slice.

some wounds are meant to be left alone

others pray we

return and return and return to them til we

turn turn turn turn turn turn turn turn

what this body do for you?

show you the infinite.

nothing more

nothing less.

——————————————————

“To argue that the imagination is or can be somehow free of race—that it’s the one region of self or experience that is free of race—and that I have a right to imagine whoever I want, and that it damages and deforms my art to set limits on my imagination—acts as if the imagination is not part of me, is not created by the same web and matrix of history and culture that made ‘me.’”

--Claudia Rankine

NOT UP FOR DEBATE

That White Supremacy exists as a system that hurts

us all and disproportionately hurts people of color.

That White people have a responsibility to dismantle

White Supremacy

That Racism + Colonialism are linked and so Racial

Justice + Decolonization are also linked

It’s not IF Racism, Colonialism and White Supremacy

exist in our community and nation it’s HOW we intend

to address and fix it

That systems of oppression exists as one overarching

matrix of domination. Oppressions intersect and are

interlocking.

People experience and resist oppression on a personal,

communal and institutional level

NORMS FOR SPEAKING

AND SHARING SPACE

Use “I” statements

Respectful communication

Assume best intention

What’s your exit strategy? / Self-care

Ouch/Oops

Take space, create space (for others)

“Yes, and” instead of Yes, But”

Engage person-first language

Indian History

They lived in teepees and wigwams, she said,

reading from the coloring page. (I was in first-grade

learning history.) They used primitive

weapons, and lived here, before they left.

I colored feathers and stalks of corn. It was

October; we had to dress up as characters from

books. When she handed me Indian in the Cupboard

I didn’t say a word – This would be perfect for you, she said.

Brown, dark-haired, I must have looked

just like that little figurine standing proudly

on the cover of the hard-backed book. At home, my mother

stuck feathers in my hair, and helped me decorate a brown

paper grocery bag with finger paint, to wear as a

costume, marching through the school, on Halloween.

Animated with smiles and march, I held the text in

my hands in front of my stomach. I vivified the tale

my teacher spun, pushed into the cupboard to become

something I was not. It was a tale rewritten out of

convenience. I couldn’t question it.

̶ Bhumi B. Patel

“Art institutions will continue to protect whiteness because they are designed to protect whiteness.”

--Aruna D’Souza

——————————————-

Finding Queer Family Among Ghosts

By Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Ghosts have been ever present in my life. I grew up in a family that stressed the importance of memory as an act of resistance, a word that has been appropriated by American liberals; it has become a catch phrase, limp in the age of Trump, so I will add to it the word resilience. Memory is an act of both resistance and resilience and remembering slain heroes was especially important.

I was born in Damascus, Syria and grew up in Karachi, Pakistan to a Lebanese mother and Pakistani Iranian father. My mother had grown up in civil war Beirut, my father, in an intensely political family, he had seen both his father executed and his younger brother assassinated by the time he was my age now, 28. When I was 18 years old and left Pakistan to study and eventually live abroad, my father and aunt had also both been assassinated. In the absence of my father’s entire generation I learned how to find family in ghosts, how to say ‘Good night, I love you’ to imaginary translucent smiling spirits, my grandfather, my uncle and my father in particular. Today, I call the Bay Area home and continue to build queer family among the living. They are my friends, people I can never hide anything from, people I trust and love. Yet, the morbid child that still lives in me cannot help but look for that kind of love beyond the grave. As an artist my practice is concerned with reviving histories of collective resistance (and resilience) and queering them through a futurist re-telling. In my research I chanced upon Jean Genet’s Un Chant d’amour, a film made in 1950, as well as Shaheed Sana’a Mhaidli, a martyr of Lebanon's civil war. Mhaidli and the characters in Un Chant d’amour became a part of my queer family, a necessary extension into both imagination and resurrection.

In Un Chant d’Amour, Genet recreates a French prison with a substantial population of queer male Algerians. Given the time the film was made – at the height of the Algerian resistance to the French – and the anti-imperialist writings of its creator, one can assume that these folks are in prison for being uncooperative with the French government. Sexual frustration is rife but so is a deep yearning for love. There is no dialogue in the film, only music. Buried deep among the heat of men masturbating alone in their prison cells are two inmates who strive for a relationship despite the walls between them. They communicate as best they can; blowing their cigarette smoke into straws they delicately slide into the tiny hole in the wall they share passing smoke from one mouth to the other without ever touching.

Watching the two men is the French prison guard who peeks through an opening in the door, moving from one cell to the other. The guard is enraged, anger builds up inside of him and you realize it is jealousy that drives his resentment. He desires one of the two lovers but knows it is a love he can never obtain and so it turns into a destructive energy, consuming him. Imagining them outside of the walls of this prison, together, in love, free and being able to actually touch one another infuriates the prison guard even more. He charges into one of the cells and begins beating the older more Algerian looking lover, whipping him with his belt as the prisoner laughs in defiance.

The struggle here is not simply one of nationalism but also of sensual love, of the revolution that lives inside pleasure and joy despite the all the barriers. The fact that two brown Algerian men can love each other even through the walls of their solitary confinement angers the white French warden, it encapsulates the very essence of resistance against the patriarchy. In my mind, the unnamed Algerians in this film become my queer elders, they are teachers, instructing by example and providing precedent to the possibilities of queer liberation outside of the Anglo-Saxon world.

While the figures in Un Chant d’amour are queerly presented, Shaheed Sana’a Mhaidly died before the world could have been aware of any of kind of sexuality. I ask the reader to join me in seeing queerness in a broad sense, a social and political word that is less about who you fuck and more the systems you are willing to fuck up.

Mhaidly was from the southern Lebanese city of Tyre, an ancient port that came under Israeli occupation in 1982 at the height of the Lebanese civil war. The Israeli occupation was brutal and reared its ugly head to the world after the twin massacres of Sabra and Shatila, two Palestinian refugee camps on the outskirts of southern Beirut. The Israeli army and its local allies – Lebanese ultra-right wing militia – sealed off the camps and killed 3,500 civilians. They kept the genocide a secret until the stench of the rotting bodies wafted into the surrounding neighborhoods.

This of course wasn’t the only horror of the Zionist occupation but it was likely one of many that convinced the teenage Mhaidly to join the Syrian Socialist Nationalist Party, a secular and irreligious party that was among many groups fighting the Israeli occupation. She gave up a life of familial and religious expectations to join a movement she saw as bigger than that. In 1985 she was sent on a mission: to drive a car filled with explosives into an Israeli convoy carrying weapons to strategic Israeli outposts in Southern Lebanon. She succeeded in her mission, killing herself and destroying the convoy. She has been called the world’s first ever suicide bomber.

What makers her queer? Everything. In a video she recorded before her death she sits casually, her voice unbroken and lucid. She implores her family not to be sad as the day that she dies should not be mourned as a death anniversary but her wedding day, she is marrying the soil of her home. In 2008, during a prisoner exchange between Hezbollah and the Israeli government her remains were returned to her family. Instead of a funeral, her family held a wedding procession, both Christians and Muslims took part, churches rang their wedding bells and imams symbolically read her rights as if she were getting married.

Mhaidli chose not to marry a man, she chose not to be absorbed into a society that would have defined her through who her husband or who her father was but instead she chose the earth, Mother Earth. The soil is her bride and her groom and in so doing she rejects expectation and mainstream society, intentionally placing herself on the margins of what it means to be a woman, she becomes politically queer. In the eyes of much of the West, even to liberals and progressives, her actions may be dismissed as unnecessary agitation again placing her on the margins of resistance.

——————————————-

Car-Boot

We mourn old things, dented steel cups

engraved with A.K. Patel, the first-wedding

silver, the India-Pakistan partition.

We work, trying to fill

the space and yet empty it. We save

what we can, in the garage-turned-museum,

filling the newly installed shelves, creaking

under the weight, and making a pile

called “Car-boot sale” in a translucent,

pink, plastic bin. Shaking faded bath

mats outside the house, each of us

sneezes in turn, as dust swirls up

and into the sunlight, escaping from

this place. Early evening, we lock

each window and draw the net

curtains, then the thick curtains,

preparing to take our leave. My bhabhi

sweeps up the bits of peeling dried

wallpaper, and more dust from

boxes, squatting on her knees

with a short broom and dust pan.

All day we worked, unable to make this

place anymore full, or empty

than it had been before.

̶ Bhumi B. Patel

——————————————-

Spatial Politics

By Raissa Simpson

Black bodies are in crisis in San Francisco. Despite its reputation as a bastion for diversity and technology innovation, only a dwindling population of 3%-6%, or approximately 40,000 African Americans, remain among 800,000 residents. That is to say, Black dancers are rarely able to afford rent in a city where a salary of $100,000 per year is considered low-income. While the economic needs of San Francisco serve corporations like Twitter, Uber, and Airbnb through developers, infrastructure and resources, I came to understand a great digital divide while working in the historically Black neighborhoods of the Bayview/Hunters Point, Tenderloin and Western Addition districts.

Place, in itself, is a metaphorical false notion of security. Spaces have blood memories. As African American residents are moved out of the area, it sums up a type of traumatic by-product generated by rich white tech workers who want to move into these areas for its culture, but instead, end up pricing out the people that make up that culture.

Herein lies the dilemma for Black Choreographers: how to explore a new type of modern-day colonization? I tackle this issue in Codelining (coding plus redlining), a multi-year work exploring the digital divide and access to technology. Codelining presents and represents the authenticity of movement through Black embodiment to explore the out-migration of African Americans from San Francisco due to the very coding tech industry that hopes to provide technological access to those same Black bodies. Through this work, I want to understand the future through Black embodiment.

Gathering a group of Black bodies on stage has been an exercise in aptly compensating the Artists. Some Black dancers have traveled 50-75 miles to take part in the work. They did not want to miss out on one of the few opportunities available to tell their stories through movement. In addition to the Black cast, there have been dancers of other racial backgrounds participating, listening, and supporting the creation of the work, which has led to the topical nature of Codelining, the intersectional discussions among the cast played out with a type of carefulness.

Though much of Codelining is set in an Afro-dystopia in the future - some of which is generated through historical slave narratives - the process sources my own experience combined with personal stories from San Francisco’s Black residents. I gather these present-day stories to provide an emotional arc for the work and to foreshadow ominous events to come. Imagine having an experience with a particular issue involving how technology reshapes neighborhoods only to find out a large portion of residents in the area share the same sentiment. These personal stories add up to a shared memory and a collective link to the past and present. They also create an entry point with some forbearance into the future. Creating this living and breathing body of work with respondents happens in four stages: forming a relationship; building a level of trust and chaos; disorienting current meanings and definitions; building a space for the future.

The creative process includes a cultural strategy to interview, dialogue, and re-imagine fiercely held narratives around liberal rich residents, most of whom are White, moving into Black neighborhoods, thereby pushing out some of the poorest residents outside the City. Then capturing these stories from these displaced poor residents before they disappear. In some instances, the project has has engaged with White tech workers. However, these interactions oftentimes play out as a public relations stunt of great performativity; tech workers fear being seen being seen as the catalyst for ethnic cleansing in the areas they inhabit. All of these stories, taken together, form a figure that addresses larger themes of race and spatial politics.

Black respondents are members of the public, ages ranging from 12 to Adult, whose neighborhoods face hyper-gentrification from the tech boom. These varied perspectives are divided into age groups and occupations like student, tech worker, and so on to engage the public in Codelining’s thematic storytelling. In the dance, members of the cast are also asked to contribute their conscious decisions to live or leave San Francisco. We take time to learn how respondents engage with tech on a daily basis. We explore how each individual body navigates social interaction with technology. We also examine how those same bodies suffer the perils of gentrification’s ethnic cleansing as a result of the economic power of that same technology.

Gathering the stories of these young participants gestures towards predicating an ideal vision for the Bayview neighborhood. Young people in the Bayview navigate these issues like cosmic observers throughout the dance, as if to forebode a dystopian society where the very humanity of its residents are at stake. As the artist, it's a refreshing break from searching the historical record. Codelining looks beyond human timelines to find the very essence of the bodily spirit in Black bodies. I feel like my abstract choreography can be a catastrophic closure for the real and lived experiences of the neighboring residents. Perhaps these stories offer a sort of confluence of the truth and reality. Or maybe they illuminate how the young residents know not what the future may bring and in this, need to design their own future. I deal with these disparities on a daily basis. As the artist, I am asking the performers in the work to manipulate this lack of resources as a type of escapism. An escapism bound by imagining a future filled with abundant possibilities.

——————————————

Unedited, Unfiltered Musings:

Ramblings from the heart, body, & mind

of a Latinx Choreographer

I’m not sure how to even begin writing about this subject except that in the field of

modern/contemporary dance, a field in which bodies are the medium from which we create, use, manipulate, express from, and live off from, mine often feels to be invisible to mainstream producers, grantors, curators, presenters, corporate donors, directors, and other choreographers and dancers.

I often wonder what diversity means for many of my white choreographer & dance colleagues. Why is it that for many of them the extent of diversity representation takes the shape of white women or gay white males? And why am I supposed to be satisfied by that as a brown, gay, Latinx person.

I created a modern dance company after years of starving for non-white experiences in dance. This has been labeled a “niche.”

As I watch dance performances with my brown-colored existence, I often wonder if the 2 non-white bodies (usually 1 Black person, 1 Pan-Asian person; tokenism?) on stage were asked by their choreographer/director how their experience as POCs differed from those of their white counterparts regarding the concept being presented……. Can I see that show please?

I was once told, by a white man, not everything is about race.

Is a brown or black body on a modern dance stage an act of resistance?

Is a brown or black body on a modern dance stage an accommodation to political correctness? Does a brown or black body on a modern dance stage have agency or do we become a mere extension of white experience via the “white gaze”?

I have been told that I sound bitter.

Just another way of saying “Angry (POC - fill in blank) person”.

If you refuse to acknowledge my cultural existence in this field then why do you keep inviting me to come watch your productions? Is your positionality that much more interesting?

I once heard someone explain that most modern dance can be categorically called white dance….I have not forgotten that statement.

I crave to engage in uncomfortable but real conversations about race, equity, casting choices, production support, and your role, as well my own in this field.

This isn’t a pity party or a need for white validation. It’s a battle cry and rallying call!

--David Herrera

——————————————-

Notes & Questions from Gerald Casel

excerpted from conversations throughout the year

Race informs all aspects of artmaking, but we don’t talk about it.

One approach is to look at statistics. I’m starting that process.

So that I can say: I’m not making this up.

How do we create an atmosphere of openness through shared practice?

I made up the term “co-interrogators” for the members of the Dancing Around Race artist cohort as a way to dispel or dismantle hierarchy.

What does allyship mean?

“What do you expect?” is something I keep being asked about this project. I don’t know what to expect and I don’t know what I want. I don’t want to impose anything upon it.

There’s an assumption that the Bay Area is so woke and diverse, but the reality is otherwise.

As the Bay Area’s demographics shift, how are cultural centers dealing with that?

What is the responsibility of presenters to local artists? How do you de-centralize curatorial practice? You turn it over to other folks, other voices. Why doesn’t this happen much in the Bay Area

Whiteness is a socially constructed term. You can identify as white or you can dis-identify as white. You have a choice.

How can I lead with subtlety and precision? How can I do it without yelling?

How does institutional code-switching work? How does the language of equity change depending on who is speaking and who the audience is?

If an organization wants to be an ally or accomplice for equity, how can this work be artist-driven?

When there is a white guest speaker in the room, how can we de-center whiteness?

The dance you think you are making is being read by someone who is reading it through a racial lens. We don’t have a choice to unmark ourselves.

I’m not interested in educating people.

Why is this issue so hard to talk about?

——————————————-

White Supremacy Culture

Excerpted from Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups,

by Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun, ChangeWork, 2001

This is a list of characteristics of white supremacy culture which show up in our organizations. Culture is powerful precisely because it is so present and at the same time so very difficult to name or identify. The characteristics listed below are damaging because they are used as norms and standards without being pro-actively named or chosen by the group. They are damaging because they promote white supremacy thinking. They are damaging to both people of color and to white people. Organizations that are people of color led or a majority people of color can also demonstrate many damaging characteristics of white supremacy culture:

Perfectionism

Sense of Urgency

Defensiveness

Quantity Over Quality

Worship of the Written Word

Paternalism

Either/Or Thinking

Power Hoarding

Fear of Open Conflict

Individualism

Progress is Bigger, More

Objectivity (the belief that there is such a thing as being objective)

Right to Comfort (the belief that those with power have a right to emotional and psychological comfort)

One of the purposes of listing characteristics of white supremacy culture is to point out how organizations which unconsciously use these characteristics as their norms and standards make it difficult, if not impossible, to open the door to other cultural norms and standards. As a result, many of our organizations, while saying we want to be multicultural, really only allow other people and cultures to come in if they adapt or conform to already existing cultural norms. Being able to identify and name the cultural norms and standards you want is a first step to making room for a truly multi-cultural organization.”

—————————————————————-

Dancing Around Race is HMD's Bridge Project 2018-19 Community Engagement Residency. The Dancing Around Race artist cohort is: Gerald Casel (Lead Artist), with Raissa Simpson, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Sammay Dizon, Yayoi Kambara, and David Herrera. Dancing Around Race’s Program Coordinator is Bhumi B. Patel. HMD’s Artistic Director is Hope Mohr.

HMD's Bridge Project approaches curating as community organizing to convene equity-driven cultural conversations. HMD’s Community Engagement Residency provides sanctuary and opportunity for artists who identify as coming from the margins. For more information visit hopemohr.org

Funding for Dancing Around Race comes from San Francisco Arts Commission, San Francisco Grants for the Arts, Center for Cultural Innovation, California Arts Council, the Kenneth Rainin Foundation, and individual donors.