by Hope Mohr

Craft: Skill in planning, making, or executing

Formalism: Concern with form and technique rather than content in artistic creation

Interrogating Aesthetics

Once after a dance show, I turned to a colleague next to me and said, “That was really well-crafted.” “Yes,” she said. “But all you could see was the craft.”

Craft is not enough.

Many people advocate that in order to move the dance field toward equity, we should abandon criteria like “artistic excellence,” “mastery” and “virtuosity” in choosing what art to make and support, arguing that these words have been codes for art that conforms to Western European, patriarchal, heterosexist norms. Yvonne Rainer refused mastery and virtuosity in her influential “No Manifesto.” But however much these post-modern refusals and their progeny have democratized dance vocabulary, they have not done so for the dance field as a whole.

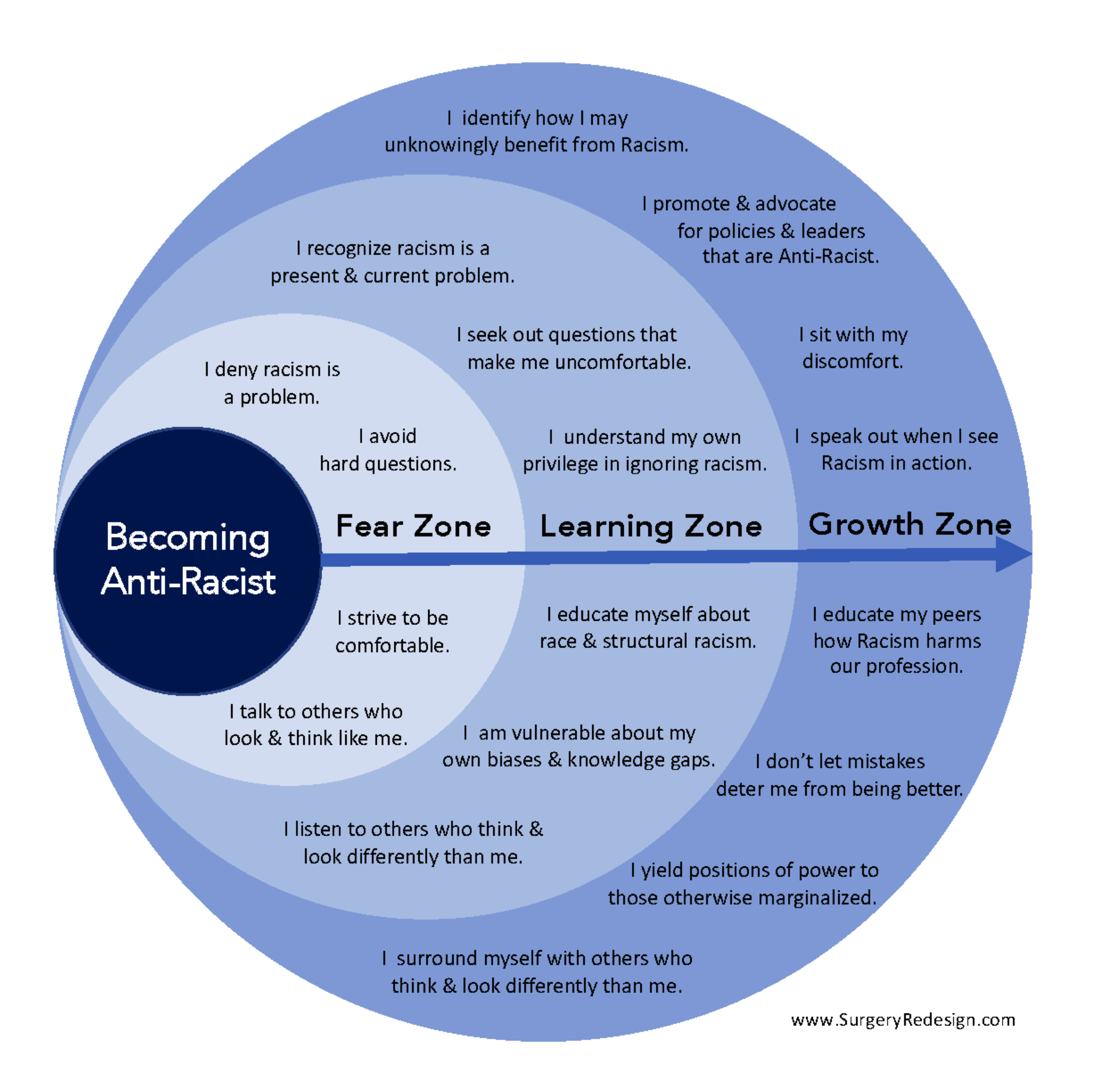

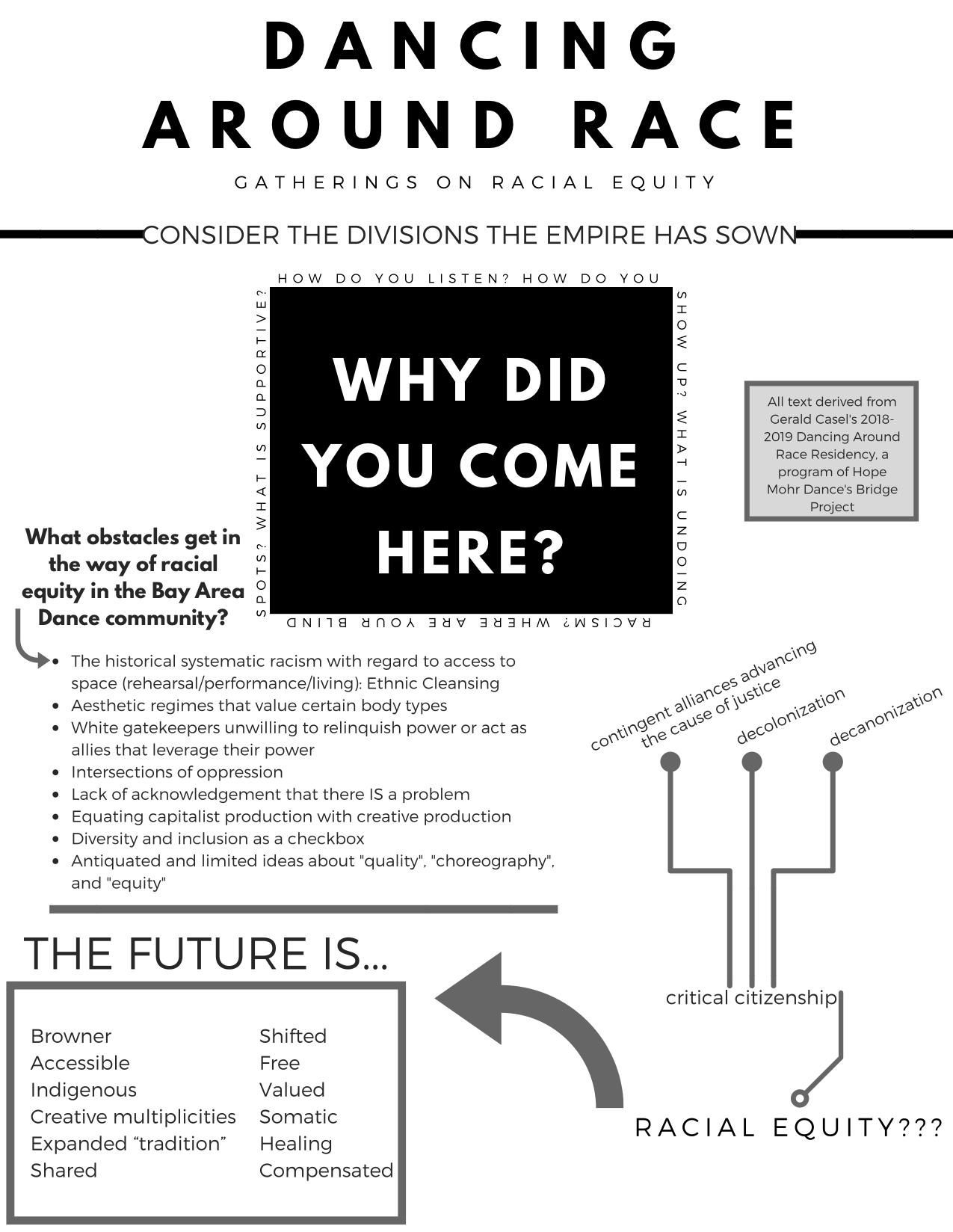

If we accept that the frame of mastery is steeped in patriarchy and control, what questions might we ask instead to evaluate art? Some possibilities, gleaned from recent conversations with colleagues, most recently at the Rainin/Hewlett Foundation’s New Pathways for Artists convening (small group discussion on decolonizing the field) and HMD’s recent Dancing Around Race public gathering:

Is the work authentic?

Does it promote freedom?

Is it necessary or urgent?

Does it positively impact the community?

Does it promote joy and pleasure?

Is it relevant or contemporary?

Does it make me feel something?

What does the work risk?

Aruna D’Souza, at the recent Dancing Around Race gathering, noted that the issue is not whether or not we should abandon standards of artistic excellence, but whether we can adopt different standards. For example, hip hop has its own standards of excellence that differ from those used to evaluate ballet.

I undertake this inquiry to, in the words of Claudia Rankine’s Racial Imaginary Institute, “question, mark, and check” my whiteness, to challenge white dominance as it operates through default positions in my cultural behavior. This reckoning demands that I examine my aesthetics. When I say aesthetics, I mean my ingrained sense of what is good art and who is a good artist. I also mean what I put out into the world as an artist.

This reckoning can begin by asking ourselves, in Rankine’s words: is my imagination my own? When I was a very young girl, even before my first dance class, I liked to walk up and down the hallway of our apartment touching the walls on either side with my fingertips, crafting pattern. Those patterns came from inside of me, not from some internalized system of oppression. I’m not a fascist because I like craft. That doesn't mean I shouldn't be interrogating the roots of my preferences. This inquiry can begin by recognizing my cultural and artistic lineages. White supremacy pervades my aesthetic evaluations because it is at the foundation of this country and I can't get away from it. When I watch and make dance, I see patterns in time and space. Those patterns are a function of my whiteness.

I want to argue that dance, as a form, can be liberated and liberating through committed and thoughtful practice. I want to argue that when form is liberated, it then can also be liberatory by demonstrating the kind of thorough application of ethics that might make all of us better citizens. A thorough application of ethics in relationship to our craft must examine the integrity of the relationship between our form and our content. I want to ask myself—to ask ourselves—if we are borrowing heat from politically trending subject matter and then skating by with forms we know will be palatable to a Western concert dance audience?

Craft can and should be a function of research and inquiry. I want to anchor this inquiry in the work of Adrienne Rich, a lesbian feminist who wrote extensively about the possibilities that sit at the intersection of politics and poetry. Adrienne Rich writes, in her essay Rotted Names:

“[W]hiteness—as a mindset—is bent only on distinguishing discrete bands of color from itself. That is its obsession—to distinguish, discriminate, categorize, exclude on the basis of clearly defined color. What else is the function of being white?...[P]eople have defined themselves as white, over and against darkness, with disastrous results for human community.”

Similarly, Adriano Pedrosa writes: "Straight society is based on the necessity of the different/other...But what is the different other if not the dominated?" (Adriano Pedrosa, What is the Process," in Ten Fundamental Questions of Curating.) As an artist, how can I develop forms and structures that do not depend on dualisms, binaries, hierarchies? How can I "discover other models and theories beyond the Euro-American toolbox of abstraction, pop, minimalism, conceptualism, the grid." Pedrosa answers: "To learn new tools we might need to unlearn old ones."

How do we unlearn our approach to craft? Visual thinking is often rooted in difference. But embodied thinking—sensation-based thinking—is less tethered to difference. Dance’s unique power sits at the intersection of seeing and feeling. The craft of choreography has the potential to subvert dominant modes of thinking by infusing the visual with embodied knowledge.

Rich writes, in her essay “What Does a Woman Need to Know?”:

“It was only when I could finally affirm the outsider’s eye as the source of a legitimate and coherent vision, that I began to be able to do the work I truly wanted to do, live the kind of life I truly wanted to live, instead of carrying out the assignments I had been given as a privileged woman.” (emphasis mine)

What does an outsider formalism look like? Or as dancemakers, let’s ask: what does an outsider formalism feel like?

Case Study: Hinterlands

On August 17, 2018, I went to see the premiere of John Jasperse’s new work Hinterland at Hudson Hall in upstate New York. The cast of five featured DeAngelo Blanchard, Eleanor Hullihan, Mina Nishimura, Antonio Ramos and Jasperse. The description of the work on Jasperse’s website reads: “A varied group of dancers, including Jasperse, comes together with a commissioned score by Hahn Rowe, to build a micro-community, where dance is both a celebration and a refuge from the wreckage of culture and history.”

The work was performed in the round. The dance space was marked off with a large square of hot pink gaff tape containing many intersecting lines. At times during the work, the dancers traveled along these lines. At other times, the lines appeared irrelevant.

The performance began with a body (Hullihan) hidden under a beautiful piece of fabric. Hullihan manipulated the fabric into shapes and images, blurring the line between body and object. After this extended opening sequence, a processional entered the space: Blanchard, Jasperse and Ramos clad in flamboyantly colorful costumes that obscured the head, face and body. They were cosmonauts, Teletubbies, circus creatures, drag queens.

The work bled into the margins of the room. Entrances and exits unfurled long before and after the performers entered or exited the official performance space. About halfway through the work, two performers pulled up quite a bit of the hot pink floor tape and stuck it on their faces. The pink tape also demarcated a smaller box off to the side of the playing space. In this visible, marginal space, the dancers changed looks and states, rested and played with pieces of fabric.

Throughout the work, the dancing was minimal and formal. I recalled Barbara Dilley’s term “elegant pedestrian.” Post-modern (lack of) affect. There was one exuberant aerobic ensemble section of patterns and high energy, but a stripped down vocabulary prevailed.

The heart of the work was a series of duets that juxtaposed the different bodies in the cast. There was a duet between Blanchard (African-American) and Jasperse (white). Another duet between Blanchard (African-American) and Nishimura (Asian). Another duet between Hullihan (white) and Nishimura (Asian). Even the ensemble section was a high-energy reshuffling of pairs.

I can’t write about the work without noting the racial identities of the performers because the content in the work was not choreography per se, but difference. Difference in the performing bodies. If the cast had been all white, the choreography would have been boring. The choreographic content of the duets was extremely minimal—mirroring of basic shapes and simple weight shares. The duet vocabulary was not technical, ornate, complicated, or fast.

In its restrained sensibility, Hinterlands still felt like a John Jasperse work—he did not shirk authorship. But compared to work I’ve seen of Jasperse in the past (I’ve seen his California, Prone, Within Between, and just two dancers), Hinterlands was a bit simplistic. Jasperse, a skilled craftsman, had surrendered his craft to difference itself. Perhaps Jasperse was consciously choosing to take up less space as an author? Perhaps he was making a statement about identity being the only politically viable choreographic content right now? Perhaps he was trying to situate or mark his whiteness by foregrounding difference? In any case, identity and craft blurred.

Aesthetic Unities

Many white people don’t need to think of identity on a regular basis. The term “identity” is rarely applied to whiteness:

“Racial identity is taken to be exclusive to people of color: When we speak about race, it is in connection with African-Americans or Latinos or Asians or Native People or some other group that has been designated a minority. ‘White’ is seen as the default, the absence of race.’"

--Laila Lalami, Group Think, New York Times Magazine, November 27, 2016.

The aesthetic corollary of the whiteness-as-neutral fallacy is that white artists working in abstraction tend to take unity of form and content for granted. In contrast, artists of color often must fight to legitimize their abstractions. Zadie Smith writes, of African-American painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye:

“Yiadom-Boakye is as committed to her kaleidoscope of browns as Lucian Freud was to the veiny blues and the bruised, sickly yellows that it was his life’s work to reveal, lurking under all that pink flesh. In his case, no one thought to separate form from content, and Yiadom-Boakye’s work is, among other things, an attempt to insist on the same aesthetic unities that white artists take for granted.” (emphasis mine)

Similarly, Hilarie M. Sheets writes:

"‘[White visual artist] Donald Judd didn’t have to explain himself. Why do I have to?” asks Jennie C. Jones, an African American abstract painter who has grappled with the issue of how her work can or should reflect her race. ‘[White visual artist] Fred Sandback can make this beautiful line and not have to have it literally be a metaphor for his cultural identity.’"

--The Changing Complex Profile of Black Abstract Painters, ArtNews, June 4, 2014.

Kara Walker, in a recent artist statement for her 2017 show at Sikkema Jenkins, expressed her fatigue from having to explain her work in terms of her racial identity as she acknowledges the inescapable weight of American racial injustice:

“I don’t really feel the need to write a statement about a painting show. I know what you all expect from me and I have complied up to a point. But frankly I am tired, tired of standing up, being counted, tired of ‘having a voice’ or worse ‘being a role model.’ Tired, true, of being a featured member of my racial group and/or my gender niche. It’s too much, and I write this knowing full well that my right, my capacity to live in this Godforsaken country as a (proudly) raced and (urgently) gendered person is under threat by random groups of white (male) supremacist goons who flaunt a kind of patched together notion of race purity with flags and torches and impressive displays of perpetrator-as-victim sociopathy. I roll my eyes, fold my arms and wait. How many ways can a person say racism is the real bread and butter of our American mythology, and in how many ways will the racists among our countrymen act out their Turner Diaries race war fantasy combination Nazi Germany and Antebellum South – states which, incidentally, lost the wars they started, and always will, precisely because there is no way those white racisms can survive the earth without the rest of us types upholding humanity’s best, keeping the motor running on civilization, being good, and preserving nature and all the stuff worth working and living for?

Anyway, this is a show of works on paper and on linen, drawn and collaged using ink, blade, glue and oil stick. These works were created over the course of the Summer of 2017 (not including the title, which was crafted in May). It’s not exhaustive, activist or comprehensive in any way.”

Perhaps liberated craft looks and feels different depending on the identity of the artist. But regardless of whether or not identity is the subject of a dance, ultimately that dance will not be fully realized—whether you want to call this finished ideal “excellent” or “impactful” —unless form is indissoluble from content. Again, Adrienne Rich:

“The power and significance of an emerging consciousness, of form discovering its meaning, form indissoluble from meaning, is the process art (as creative change) depends on—and embodies.

‘What are your poems about? a stranger will sometimes ask. I don’t say, ‘About finding form,’ since that would imply that form is my only concern. But without intuition and mutation, in each poem yet again, of what its form will be, I have no poem, no subject, no meaning.”

---Six Meditations in Place of a Lecture

Similarly, Zadie Smith writes, “Everyone is born with a subject, but it is fully expressed only through a commitment to form.” (Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Imaginary Portraits, The New Yorker, June 19, 2017) Smith quotes the African-American painter Lynette Yiadon-Boakye, talking about her artistic process:

“Over time I realised I needed to think less about the subject and more about the painting. So I began to think very seriously about colour, light and composition. The more I worked, the more I came to realise that the power was in the painting itself.” (emphasis mine)

The power is in the painting itself.

A big part of craft is committing to the material. Listening to the material. Letting it speak. A thorough application of ethics in relationship to our craft demands a dialogic process. Not a solipsistic process. Not a process of appropriation. But a process in which we go within, and then out beyond ourselves, and then back within again, and then again out past ourselves, and so on, in a constant conversation between our form and the world. I think that kind of process make sense if my liberation is bound up with yours.

Rich urges poets to examine their form “for ignorance, solipsism, laziness, dishonesty, automatic writing.” (Tourism and Promised Lands) This reminds me of Hilton Als’ recent critique of Young Jean Lee’s new play, “White Men”: “By trying to lampoon whiteness, she’s made a “white” play: shallow, soporific, and all about itself.” (Hilton Als, The Soullessness of “Straight White Men”, The New Yorker, August 6 & 13, 2018 (emphasis mine)). A liberated craft must find, in Rich's words, the “dynamic between poetry as language and poetry as kind of action, probing, burning, stripping, placing itself in dialogue with others out beyond the individual self.” (Blood, Bread and Poetry) (emphasis mine).

On the flip side, if we anchor our artmaking exclusively outside ourselves—in the desire to make the world a better place, for example—we risk disconnection from our own poetics:

“We do not trouble the waters with a language that exceeds the prescribed common vocabulary, we try to ‘communicate,’ to ‘dialogue,’ to ‘share,’ to ‘heal,’ in the holding patterns of capitalistic self-help—we pull further and further away from poetry.”

--Adrienne Rich, Tourism and Promised Lands

An arabesque has nothing to do with poverty. Our forms should exceed the prescribed common vocabulary. Dances that claim to be “about” social justice issue X (sex trafficking, poverty, global warming) and claim to accomplish this by putting a voiceover about issue X underneath their abstract dance fail as art because there is no connection between content and form. Many dances “full of liberal or radical hope and outrage fail to lift off the ground, for which ‘politics’ is blamed rather than a failure of poetic nerve.” (Adrienne Rich, in Tourism and Promised Lands).

It’s moving in the right direction to source movement from, or through dialogue with, an impacted community (or melting glacier). But the power must be in the dance itself, not borrowed heat from the subject matter. White artists cannot take unity of form and subject matter for granted. We need to summon the poetic nerve to insist on a deep dialogue between our craft and our content. Only then might our dances pulse with “an engaged poetics that endures the weight of the unknown, the untracked, the unrealized.” (Adrienne Rich, Poetry and The Forgotten Future)

——————

In this writing, I have focused on the finished work of art, not the choreographic process. The two could be related. But you can have a diverse cast and an equitable creative process and still not produce a finished work of art that contributes to societal equity. Likewise, you can make a work through autocratic methods that nonetheless promotes equity through its message.

——————

Special thanks to Megan Wright for significant contributions, Tracy Taylor Grubbs and the Dancing Around Race artist cohort.

The next Dancing Around Race public gathering is Friday, October 26th at 10:30 AM at the Joe Goode Annex. Featuring Barbara Bryan, Executive Director of Movement Research in New York City in conversation with Gerald Casel about institutional thinking and models of advancing equity in the arts.

AND

There’s a Dancemaker Clinic coming to town. A new opportunity for artistic growth and career coaching with choreographer and director Hope Mohr in ODC’s beautiful Studio B (50 feet x 61 feet). A full hour of individualized, private mentorship tailored around your needs and questions. Mentorship includes artistic feedback, production coaching, career strategy and a variety of tools to support your process. Artists can use the hour to show and document work in progress. Performance makers from all disciplines welcome. Appropriate for artists at any career stage. Monday nights at 7 and 8 PM (one slot per artist). October 22 -December 10.

SIGN UP HERE: http://odc.dance/DancemakerClinic.

References

Hilton Als, The Soullessness of “Straight White Men”, The New Yorker, August 6 & 13, 2018.

Casel, Gerald. Responding to Trisha Brown's Locus, the body is the brain, November 1, 2016

Charlton, Lauretta. Claudia Rankine’s Home for the Racial Imaginary, The New Yorker, January 19, 2017.

hooks, bell. "Postmodern Blackness,” Postmodern Culture, vol. 1, no. 1 (Sep. 1990).

Kao, Peiling. "On Per[mute]ing," the body is the brain, October 27, 2016

Lalami, Laila. “Group Think: The Identity Politics of Whiteness,” New York Times Magazine, November 27, 2016.

Menand, Louis. "What Identity Demands,” The New Yorker, September 3, 2018.

Mohr, Hope. "Choreographic Transmission in an Expanded Field: Ten Artists Respond to Locus,” TDR: The Drama Review 62:2 (T238) Summer 2018.

Pedrosa, Adriano. "What is the Process," in Ten Fundamental Questions of Curating. Ed. by Jens Hoffman, Mousse Publishing, 2013.

Profeta, Katherine. Dramaturgy in Motion: At Work on Dance and Movement Performance, University of Wisconsin Press, 2015.

Racial Imaginary Institute

Rankine, Claudia “Teju Cole’s Essays Build Connections between African and Western Art.” New York Times Book Review, 9 August:12, 2016.

Rich, Adrienne. Essential Essays: Culture, Politics and the Art of Poetry. W.W. Norton & Co. 2018.

RIFF TALKing on Identity and Performance, with Jaamil Olawale Kosoko, Joy Mariama Smith, Sara Smith and Tara Aisha Willis; moderated by Cassie Peterson. Originally printed in Contact Quarterly, Vol. 42 No. 2, Summer/Fall 2017.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2016.

Sheets, Hilarie M. The Changing Complex Profile of Black Abstract Painters, ArtNews, June 4, 2014.

Smith, Zadie. “A Bird of Few Words: Narrative Mysteries in the paintings of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.” The New Yorker, June 19, 2017.